Visual identity is not cosmetic — it’s a leadership decision

When a company’s visual language no longer works, the wrong questions are usually asked — Is the colour wrong, has the logo fallen behind its time or even, did the designer fail to capture the intended idea or taste?

Much more rarely is attention paid to where the problem actually began — whether anyone in the organisation has consciously decided what the visual language should be, how it should evolve over time, and who is responsible for the company’s visual direction.

Visual identity is not created in design tools — it is implemented through decisions.

Visual problems are rarely design problems.

They are decision problems.

As a company grows, channels multiply, partners change, campaigns come and go. Every new situation requires a visual output. When earlier decisions have not been fixed, each new campaign or design need results in something “approximately suitable”. Not out of bad intent, but based on best judgement at the time. The result is not one bad design, but gradual visual fragmentation that accumulates quietly and often unnoticed.

The real question is not who designs, but who makes decisions with the visual whole in mind.

Marketing needs campaign materials quickly, product teams need packaging, sales needs presentations, partners need logos. When visual identity has not been agreed upon, everyone solves their own immediate need. Designers improvise, marketing optimises, product adapts. No one is doing anything wrong — but no one is steering the whole. This is where the illusion arises that the problem lies in design. In reality, the problem lies in indecision.

Visual identity is not the place where decisions are invented. It is the place where decisions are applied. When decisions exist, work moves quickly and consistently. When they don’t, every new output becomes a discussion, a compromise, or a temporary fix that solves the moment but creates the next problem. In this sense, visual identity is not cosmetic — it is structural. Just as architecture does not re-decide the position of walls at every doorway, a company’s visual language should not depend on the mood of each individual project.

This is where a Corporate Visual Identity guide — a CVI — becomes relevant. Not as a thick book or rigid rule set, but as a tool for fixing decisions. A CVI does not dictate how everything must look. It clarifies what is no longer debated: the role of the logo, when colour becomes an issue, when variation is acceptable and when it is not. It creates a framework within which flexibility is possible without the identity falling apart.

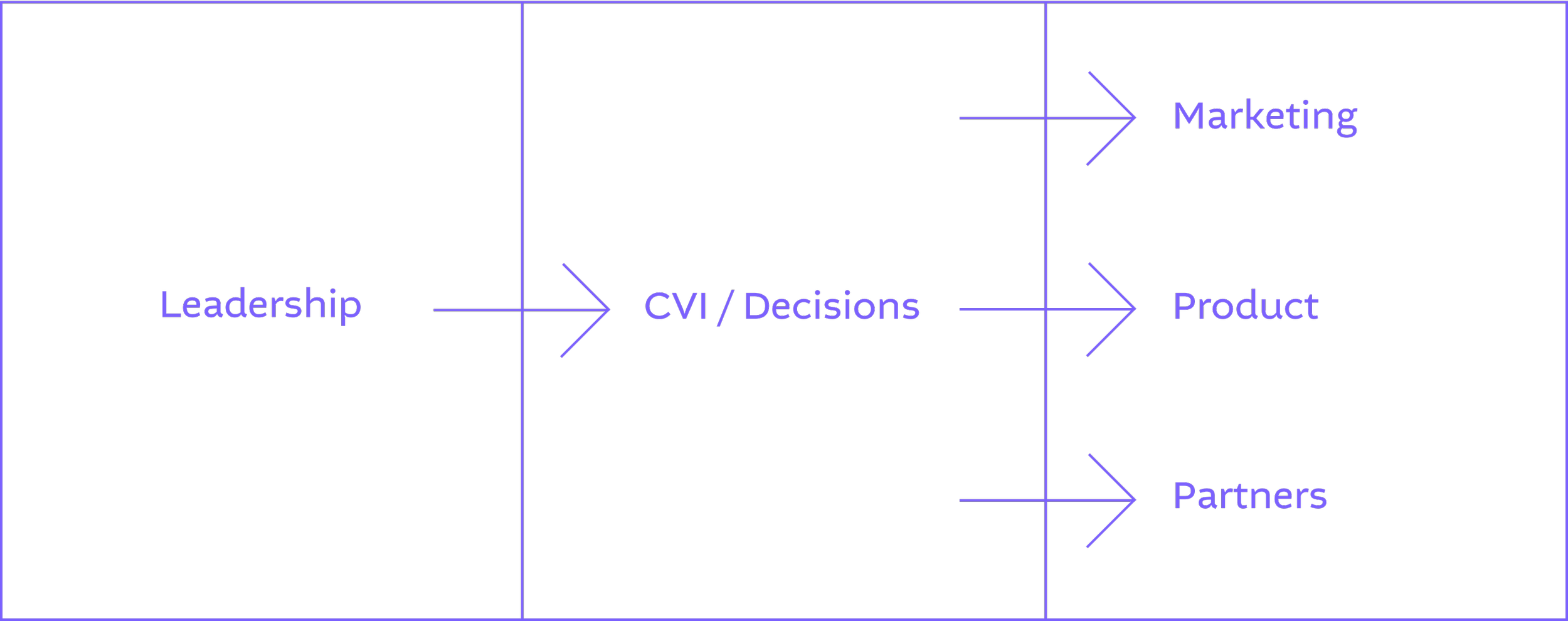

From a leadership perspective, a CVI is not a design document but a management tool. It reduces decision fatigue, accelerates processes, and prevents the same debates from recurring again and again. From the perspective of marketing and product teams, it provides confidence that each new output does not start from zero or depend on who happens to be making the request.

Failing to make decisions is often more expensive than making the wrong design choice. Poor design is visible and can be corrected. Indecision is costly in silence — in time, energy, rework, and ultimately in brand perception. Visual confusion does not create outrage; it creates indifference, which is far more dangerous for a business.

Good design is not born from tools or trends. It is born from choices — what to leave out, what to emphasise, and what kind of system to build so it lasts longer than a single campaign. Visual identity and CVI are communication tools, both internally and externally. They are a decision about how a company presents itself, how it is recognised and repeated, the language it speaks from campaign to campaign, and the consistent path followed by products, services and people. It is a direction agreed at leadership level, not an accidental outcome.